Warming Dots

July 2018

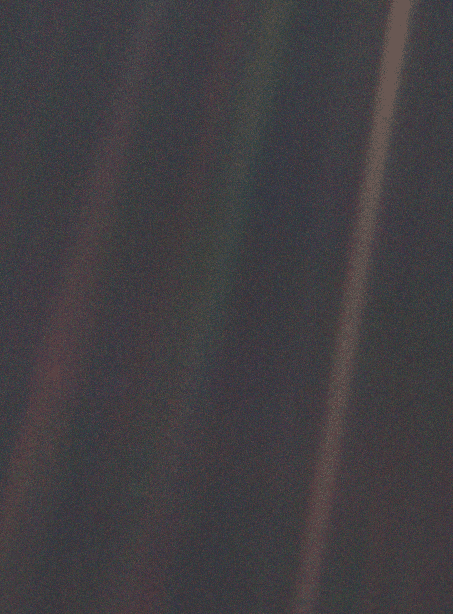

Sometimes, when the problems of the world seem overwhelming, it's worth remembering how small we really are. Physicist Carl Sagan summed it up nicely when commenting on a 1990 image of the Earth taken by the Voyager 1 space probe, titled Pale Blue Dot:

The Earth is a very small stage in a vast cosmic arena. Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors so that in glory and in triumph they could become the momentary masters of a fraction of a dot. Think of the endless cruelties visited by the inhabitants of one corner of the dot on scarcely distinguishable inhabitants of some other corner of the dot. How frequent their misunderstandings, how eager they are to kill one another, how fervent their hatreds. Our posturings, our imagined self-importance, the delusion that we have some privileged position in the universe, are challenged by this point of pale light.

From this perspective, it's hard not to feel insignificant. This may be cold comfort, but in a twisted way it's sort of comforting. It makes a lot of the problems that we're facing seem less significant as well. After all, what's the worst that can happen? We fail as a species, and the universe marches on.

But the Pale Blue Dot perspective is about more than just nihilism. It can also help frame some of our global issues in a new light. Take global warming, for instance. The surface of the Earth is warming because of human activity, and we're at a point where our survival as a species is jeopardized because of the rapid changes we've made to the planet.

On the one hand, if Earth is nothing but a pale blue dot, global warming is just one of any number of planetary issues that, on a cosmic scale, don't matter. But on the other hand, if Earth is nothing but a pale blue dot, then maybe there's nothing unique about it. And if there's nothing unique about it, maybe global warming itself is a phenomenon that could exist elsewhere in the universe, on other planets that host technological civilizations. And if that's the case, maybe there's something we can say about global warming across those planets, and make some guesses about how things might shake out here at home.

This is the perspective of astrophysicist Adam Frank and his colleagues, who recently published a paper exploring exactly this idea. If we are not unique in the universe, then perhaps are problems aren't so unique either: in this case, rather than being insignificant, perhaps issues like global warming are themselves common across the universe.

In their paper, the authors propose a few general models of how an issue like climate change could impact a civilization. In this story, I'd like to highlight some of those models in an interactive way. But before we get there, we'll need to talk a bit about in what sense global warming is a problem, and dust off some simple mathematical models that you may have not used since high school.

Global Collapse

At the risk of sounding silly, what's the problem with global warming, anyway? Warming on its own doesn't necessarily have negative connotations.

The problem is less about the warming itself, and more about the consequences of the warming. In particular, the changes we are making to our climate yield incredibly sobering predictions; it's clear that we're changing our planet faster than the speed at which many species (including us) will be able to adapt. In other words, global warming is primarily concerning because of its potential for global collapse. This collapse can take many forms, including destroyed ecosystems and mass extinctions.

It's the extinction part that will be our focus here. Put more succinctly, global warming kills. The question is, how successful will it be, and what steps can we take to try to combat it?

In order to answer these questions, we first need to model how a population grows with time. There are many different models we could use. Let's start with the simplest, highlight its deficiencies, and gradually roll out improvements.

Exponential Growth

One of the first models of population growth that people encounter is one of exponential growth. For example, here's a slightly modified version of a word problem you may have encountered during your formative years:

A scientist puts 10 bacteria in a petri dish. An hour later, there are 20 bacteria. An hour after that, there are 40. How many will there be in another 3 hours?

The key observation here is that the doubling time in this problem is an hour: every hour, the population of bacteria doubles. This constant doubling time is a hallmark of exponential growth.

Closely tied to the idea of a doubling time is a constant called the growth rate. These two things are inversely proportional to one another: The higher the growth rate, the shorter the doubling time, and vice versa.

Here's an example of an exponential growth curve for a hypothetical population. You can adjust the growth rate and see how that affects the shape of the curve: more specifically, how quickly it shoots up.

Growth rate for the population

Figure 1: An exponential model of population growth.

The problem with an exponential growth model of population is that while it may be suitable for short-term predictions, there's no way for it to be make sense longer term. In the word problem above, for instance, the bacteria will eventually be limited by the size of the Petri dish.

Exponential models of human population suffer from a similar flaw. We live in a world with finite resources, and barring revolutions in interstellar travel, this imposes hard limits on how many people can exist on our planet. Exponential growth, almost by definition, is unsustainable growth. It's simply not feasible for anything to grow both exponentially and in perpetuity.

The Logistics of Tempering Growth

So if exponential growth isn't a suitable model, what is? One way we can try to modify our model is to incorporate the limits we've already addressed: namely, that any environment has finite resources.

In other words, there's a theoretical limit to the size of the population that any environment can support. This is sometimes referred to as the carrying capacity of the environment.

As a practical matter, determining the carrying capacity of any environment is a difficult problem. But assuming we know its value, we can then modify our population model to account for it. This brings us to the next most common model of population growth: the logistic function.

The logistic model of population incorporates two parameters: a growth rate for the population, and an environmental carrying capacity that effectively caps the population. Here's what the model looks like: note that the presence of the carrying capacity gives the logistic function its signature S-shape.

Growth rate for the population

Carrying capacity for the environment

Figure 2: A logistic model of population growth.

When we include a carrying capacity in our model, population no longer grows without bound. Instead, the curve begins to bend downward once the population is half of the carrying capacity, and the population will never exceed the carrying capacity. As advertised, the carrying capacity places a hard limit on how big the population can be, which seems much more realistic.

Consistent Capacity

Our first model for population lacked a mechanism to control unbounded exponential growth. Our second model introduced the idea of carrying capacity, which fixes the problem, but is still a bit of an oversimplification.

Put another way, our first model was limited by the fact that the carrying capacity was infinite. But our second model is limited by the fact that the carrying capacity is constant. In reality, the carrying capacity of a system is probably dependent on a variety of factors. It could depend on the time of year, the populations of other species in the environment, or how destructive population growth is to the environment itself.

This last idea is where Frank and his colleagues begin their interplanetary analysis. Their paper proceeds through three increasingly complex iterations of the idea that carrying capacity depends on a population's interaction with the environment. We're now prepared to tackle their first model, and see its qualitative differences compared to the models we've already considered.

Population and Environment

In what follows, we're no longer going to model population alone. We'll be modeling both population and a measure of environmental health. This environmental health metric is a bit abstract, but there are some key features we need to highlight:

- A value of 0 corresponds to the "natural" state of the environment.

- As this metric increases, the carrying capacity of the environment decreases.

- There exists some critical value of this metric, beyond which the carrying capacity of the environment is 0.

For example, we could think of this metric as being the difference between the surface temperature of the Earth and its 20th century average. This metric satisfies all of these conditions: a value of 0 corresponds to the surface temperature equalling the 20th century average, which seems like a relatively neutral baseline. (If you disagree, you could take the average over an even earlier century.)

The second condition is satisfied, too. As the surface temperature increases, the Earth becomes a more hostile place, and the carrying capacity of the planet should drop.

As for the third feature, there's undoubtedly some average temperature beyond which the planet could no longer host life. For an extreme case, we need only look to our neighbor Venus, which has blistering surface temperatures of 864 °F (462 °C), on average. Climate models even suggest that in the distant past, Venus may have been habitable, so perhaps it can provide us with an example for which the environmental health metric for the planet eventually blew past its critical value.

Note that I'm not saying temperature is the environmental health metric. The metric itself is an abstract concept. Thinking about it in terms of temperature is just a helpful way to make the idea more concrete.

Let's Get Resourceful

There's one more ingredient we need before we can explore a new model. We'll be looking at how population affects the environment, but typically the link is not direct. When it comes to global warming, for instance, population growth on its own is just a proxy for a much more significant cause: the burning of fossil fuels.

So rather than modeling how population degrades the environment, the model will explore how the harvesting of some resource both helps increase population and increase the environmental health metric. Here's what we'll assume:

- There exists some resource on the planet, with supply large enough to effectively be considered infinite.

- Harvesting the resource helps grow the population by some additional growth factor.

- Harvesting the resource harms the environment by some positive factor.

In order to graph this model, we need several parameters. Some are the same as in our pure logistic model, but there are a number of new ones as well. Here they all are:

- The natural growth rate of the population (this is the same parameter as in the logistic function).

- The additional growth rate of the population produced by harvesting the resource.

- The carrying capacity of the environment in its natural state, that is, when the environmental health metric is 0 (this is the same parameter as in the logistic function.)

- The critical threshold of the environmental health metric, beyond which the carrying capacity of the environment is 0. (More concretely, if your environmental health metric is the deviation from the 20th century average temperature, this would be the largest deviation beyond which Earth could no longer support life.)

- The recovery rate of the environment. In other words, in the absence of people, this measures how quickly the environment reverts to its natural state.

- The rate of harm to the environment caused by harvesting resources. The idea here is that this is a scale factor based on the population: the higher the population, the more resources are harvested, and the more harm is done to the environment. The larger this factor, the more harm is done per person.

Whew. That's a lot. But with all of this setup, we're finally ready to explore our third model. Here it is.

Growth rate for the population

Population growth factor due to harvesting resource

Carrying capacity in a natural (unpolluted) environment

Threshold beyond which the environment can't support a population

Recovery rate for the environment

Rate at which resource depletion harms the environment

Figure 3: Modeling Population along with the environment.

As you made expect, conditions that seem favorable yield favorable behavior. When the carrying capacity, critical environmental threshold, and recovery rates for the environment are all high and the environmental cost of resource depletion is low, the population grows in much the same way as before, even if the overall environmental health of the system worsens (as indicated by an increasing red graph).

However, things can also go south pretty quickly. For example, if the recovery rate for the environment is low, it's possible for the population to experience an early period of fast growth, following by a significant crash before stabilizing at a much lower value. While the long-term stability might seem desirable, if it comes after the wiping out of more than half of the population, this seems like a steep price to pay.

These two families of trajectories make up two of the four of the possible outcomes discussed in the paper: sustainability and die-off. Sustainability is what we'd all like to believe our species is capable of: a smooth, gradual increase in population until we reach our planet's carrying capacity. In die-off scenarios, we overshoot the carrying capacity, most of us die, and those who remain can then enjoy a stable population.

Sustainable Resources

Models necessarily simplify the real world, and this one is no exception. In their next two models, the authors try to incorporate a bit more real-world complexity.

One way to do this is by thinking more about harvesting resources. Our model currently assumes the planet has a single resource of infinite supply. But when we talk about fighting global warming, we almost never talk about ceasing all of our energy usage. Much more commonly, we talk about how we need to break our dependence on fossil fuels, and move to more sustainable sources of energy.

The next version of the model tries to capture this kind of resource transition. For simplicity, the model assumes that there exists a second resource on the planet. This resource has no negative impact on the environment, but has the same positive growth effect on population as the first resource. We'd now like to model the impact of transitioning away from the first resource to the second.

In order to do so, we need to introduce two more parameters. The first one measures our collective foresight: how much do we destroy the environment before we transition? The second parameter measures how quickly the transition occurs once it begins.

What sorts of new trajectories can you create with these additional parameters?

Growth rate for the population

Population growth factor due to harvesting resource

Carrying capacity in a natural (unpolluted) environment

Threshold beyond which the environment can't support a population

Recovery rate for the environment

Rate at which resource depletion harms the environment

How much destruction occurs before resource transition?

How long does it take to transition between resources?

Figure 4: Modeling environment and population with two resources.

Note that if you wait longer before transitioning, or take too long in the transition, in nearly every case the outcome for population worsens. Also, notice that in some cases it's possible to affect the long-term shape of the curves, switching between sustainability and die-off. From this perspective, it seems like we may have some control over our destiny even if we're late to the game, provided that we can fully transition away from fossil fuels quickly.

Environmental Fragility

But there's at least one more way in which things could potentially go awry. So far, we've always assumed that even if recovery is slow, in the absense of people the environment could heal itself eventually.

But what if that's not true? What if there's a tipping point beyond which a vicious cycle of environmental degradation begins? We need only turn to our neighbor Venus to imagine how such a scenario might play out.

For their final variation on the model, the authors included an environmental fragility parameter. The larger the value of this parameter, the easier it is for the environment to degrade beyond all attempts to repair it, even if the population is able to quickly transition to a renewable resource.

Now, with all nine parameters at your disposal, what sorts of population graphs can you come up with?

Growth rate for the population

Population growth factor due to harvesting resource

Carrying capacity in a natural (unpolluted) environment

Threshold beyond which the environment can't support a population

Recovery rate for the environment

Rate at which resource depletion harms the environment

How much destruction occurs before resource transition?

How long does it take to transition between resources?

How fragile is the environment?

Figure 5: Including an environmental fragility parameter into the model.

With the potential for environmental catastrophe, this model highlights another common scenario: collapse. This is an even worse case than die-off: not only does the population crash, but it crashes all the way to zero. This is inevitable if the environment is too fragile and becomes damaged enough that a runaway degradation occurs.

You may also discover a fourth possible outcome: oscillation. In this scenario, population growth triggers environmental degradation, which leads to a population crash. But when the population crashes, the environment begins to heal, and the population again grows. Unfortunately, this leads to more environmental degradation, followed by another population crash, and so on. While arguably better than total collapse, this seems like a less desirable outcome than a single die-off.

Conclusion

Climate change is scary, and news articles about it are almost universally depressing. But in the grand scheme of things, it may also be an inevitability; a simple consequence of a technologically advanced species that's thirsty for energy.

The authors of the paper outlined here readily admit that these models are just a starting point. There are plenty of simplifications here, and in reality, the interaction between a species like ours and the environment we live in is incredibly complex. But all models are simplifications, and even if a model doesn't capture every complexity, it can still teach us valuable lessons about our reality.

My takeaways from this model are that climate change requires swift, early action. The earlier we diagnose the problem and the faster we are to remedy it, the more likely we are to find ourselves in a sustainable population curve. And yet, even if we do everything possible to combat climate change, it's possible that the environmental deck is stacked against us, and we'll find ourselves in a less desirable trajectory.

But even if we fail, maybe somewhere up in the stars there's another pale blue dot capable of succeeding.

Sources:

Here are some other stories you may like:

Gaming Relationships: Linear Approaches

November 2017 - 8 minute read

A mathematical ballad of love and hate.

Gaming Relationships: Nonlinear Approaches

December 2017 - 7 minute read

Love, chaos, and a three body problem.

The Fairest of Them All

January 2019 - 15 minute read

A mathematical exploration of fairness.