Mind the Gerrymandered Gap

October 2018

2018 has been a big year for raising awareness on how states draw congressional districts. The Supreme Court heard two cases arguing that the way states delineate these districts is, in certain cases, unconstitutional. Pennsylvania's state supreme court said that its congressional lines violated the state constitution, and then assigned a new map when the legislature couldn't come up with one on its own. And voters in Michigan, Missouri, Utah, and Colorado can expect to vote on redistricting measures this fall.

So what's wrong with these district lines, and why are things coming to a head now? In this story, we'll outline the problem, explore some strategies for trying to detect when partisan gerrymandering has occurred, and examine some potential fixes.

A Brief Introduction to Gerrymandering

Creating districts isn't a new problem in America: it's something we do every decade, after each new census. Every state is awarded a certain number of representatives, in rough proportion to the state population, and then the state must decide how to assign regions to each representative. The state has control over how it decides to draw district lines: some do it through the legislature, some do it through independent commissions, and so on.

There are some basic redistricting rules that states must abide by, such as ensuring that each district is of approximately the same population. The Voting Rights Act prohibits states from creating districts that discriminate on the basis of race. States are free to add their own rules for redistricting (some common ones can be found here), but in general the guidelines are fairly minimal.

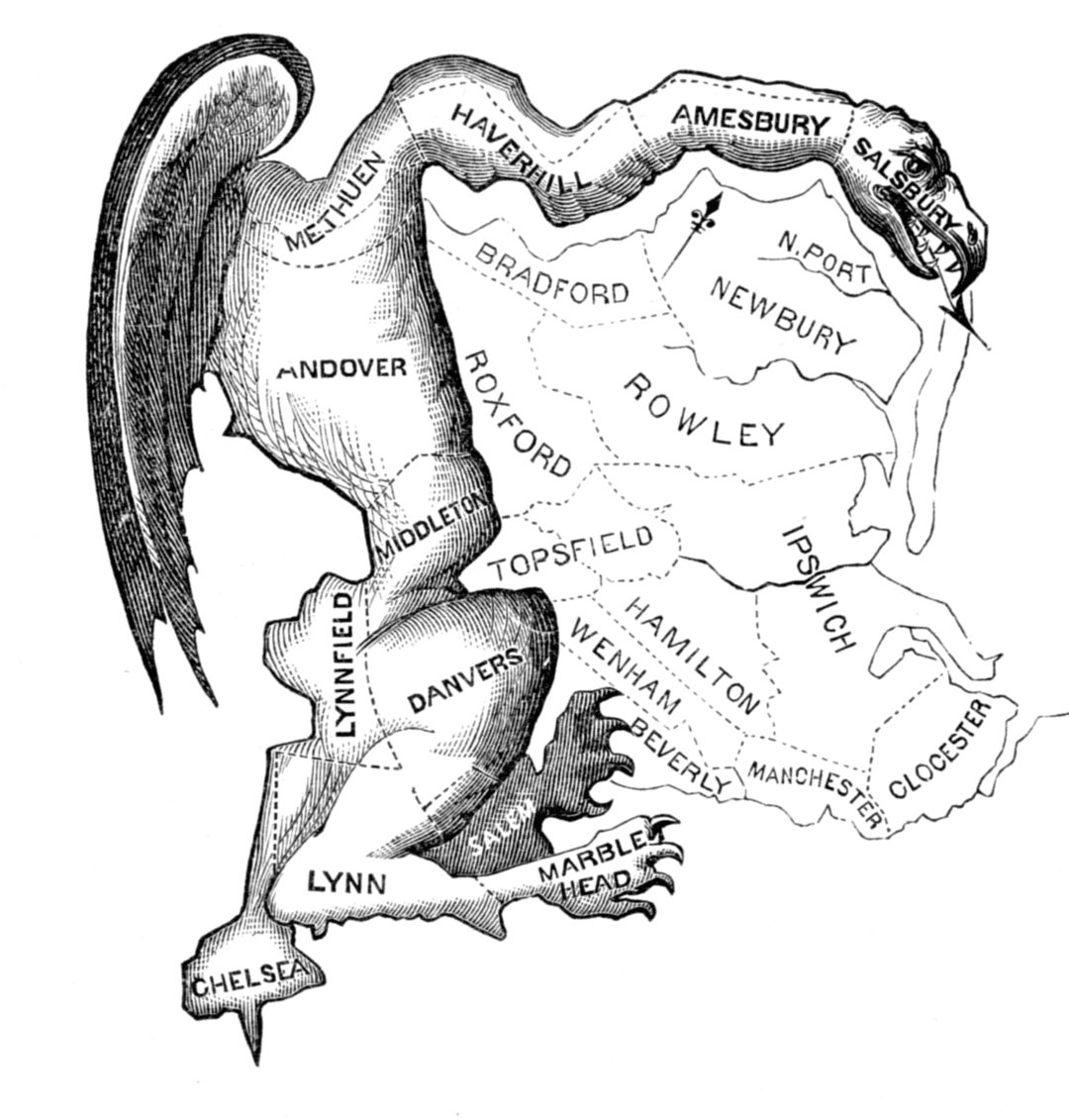

Unfortunately, this means that the process of drawing congressional lines is ripe for manipulation. And in many cases, when one party is in power, it's possible for them to draw congressional boundaries in a way that preserves or enhances their power, by exploiting geography to bolster their representation in Congress. This process, as you may well know, is called gerrymandering. The name comes from an 1812 political cartoon which drew attention to a wonky looking state senate district. The name itself is a portmanteau of the name of the Governor at the time, Elbridge Gerry, and the word salamander, as the district was said to resemble said amphibian. Gerry caught flak for the shape of this district because it was believed that the district was drawn this way to help his party in an upcoming election.

Gerrymandering for Fun and Profit! (But Mostly for Fun)

It turns out that it's not too hard to gerrymander districts. Let's take a look at a simplified example. Imagine a region with 54 citizens, evenly divided among two parties: the blue party and the red party. You are part of a committee tasked with dividing this region into six contiguous districts of the same size: nine citizens each. Each district will have a representative in the government that is elected by members from that district.

In this scenario, how would you draw congressional lines to divide this region into six districts?

D1: -- (0 blue, 0 red)

D2: --

D3: --

D4: --

D5: --

D6: --

Typically gerrymandering is achieved by combining two strategies: packing and cracking. Packing refers to consolidating large numbers of one party into a small number of districts. Cracking is the opposite: diluting the voting power of a large bloc of voters in one party by splitting them up so that they form minorities in multiple districts.

Maybe you were magnanimous and tried to give equal representation to all citizens. Or maybe you have a strong preference between red and blue, and tried to dilute the vote for one party. If you're in the latter camp, take another look at the district map you created above. Which districts are packed with voters from one party? Which districts crack up a party by making its members a minority of voters across several districts?

In this simplified example, gerrymandering isn't hard to do. It's also not that hard to detect; since the distribution of voters is evenly split, if the districts heavily favor one party over another, it's a clue that some shenanigans are probably going on.

Detecting Gerrymandering: A Brief History

Historically, gerrymandering has been treated like pornography: you know it when you see it. Districts with funny looking shapes, for example, were frequently met with suspicion.

Because of this, some of the first attempts to measure and detect gerrymandering focused on the geometry of a given district. More specifically, they often focused on the idea of compactness, the idea being that districts drawn in good faith should have a relatively compact, non-controversial-looking shape.

But while compactness has a precise mathematical definition, when it comes to drawing districts the term is more of a loose idea. Some have tried to make the idea of compactness more mathematically precise. A number of metrics have been proposed, but we'll focus on one of the simpler ones, called the Polsby-Popper test, which frames things in terms of areas and perimeters. This idea stems from an interesting mathematical fact: given a fixed length of string, the largest area you can enclose with that string will form a circle. (If you want to get fancy, this is known as the isoperimetric inequality.)

You can explore this idea yourself with the following interactive. It allows you to explore this inequality by comparing the area of a polygon to the area of a circle with the same boundary length. Use the slider to choose the number of sides of the polygon. You can then drag the edges of the polygon to adjust its area and perimeter (the circle will adjust accordingly).

Number of district sides: 0

| Circle Area: 0.00 | Polygon Area: 0.00 | Ratio: NaN |

As you can see, it's impossible to make a ratio that exceeds 1; that's the isoperimetric inequality in action. This doesn't prove the isoperimetric inequality, of course, but it should make for a convincing demonstration.

What does this have to do with compactness? Well, if you have a district of a certain area, you can calculate the length of its boundary, and then ask what the area of a circle with that same boundary length would be. By the isoperimetric inequality, the circle will necessarily have a larger area, unless the district too is in the shape of a perfect circle.

Once you have these two shapes - the district and the circle - you can calculate the ratio of the district's area to the circle's area, just as in the above interactive. The thinking here is that if the ratio is close to 1, then the district will be relatively compact. But if the ratio is very small, or close to 0, this indicates that the district is essentially making poor use of its boundary. Since there's a long, winding boundary enclosing a relatively small area, this might suggest an strangely-shaped, and therefore excessively gerrymandered district.

The Washington Post did an analysis of every congressional district in 2014 using this measure of compactness; you can find all the measurements here. For example, they found that the fourth congressional district in Illinois had a ratio of district area to comparable circle area of only 0.1596. This value, being much closer to 0, might suggest excessive gerrymandering.

But don't just blindly believe the numbers. Take a look at the district and judge for yourself:

Concerns with Compactness

Removed from context, the fourth district of Illinois looks highly suspicious. Its meandering shape through Chicago and out into the 'burbs suggests that there could be some packing going on. And indeed there is, but the reasoning behind it is different than you might expect.

Put simply, the district's shape is a consequence of the Voting Rights Act. The district combines two majority-Hispanic populations into one congressional district. The federal government mandated the creation of such a district in an attempt to remedy previous violations of the Voting Rights Act, and the constitutionality of this district has been upheld by the Supreme Court (here's a reference with more detail if you're interested).

In other words, if you're concerned about the aggressive use of gerrymandering to enhance the power of the already powerful, you need to be a bit careful about using shape alone as your metric.

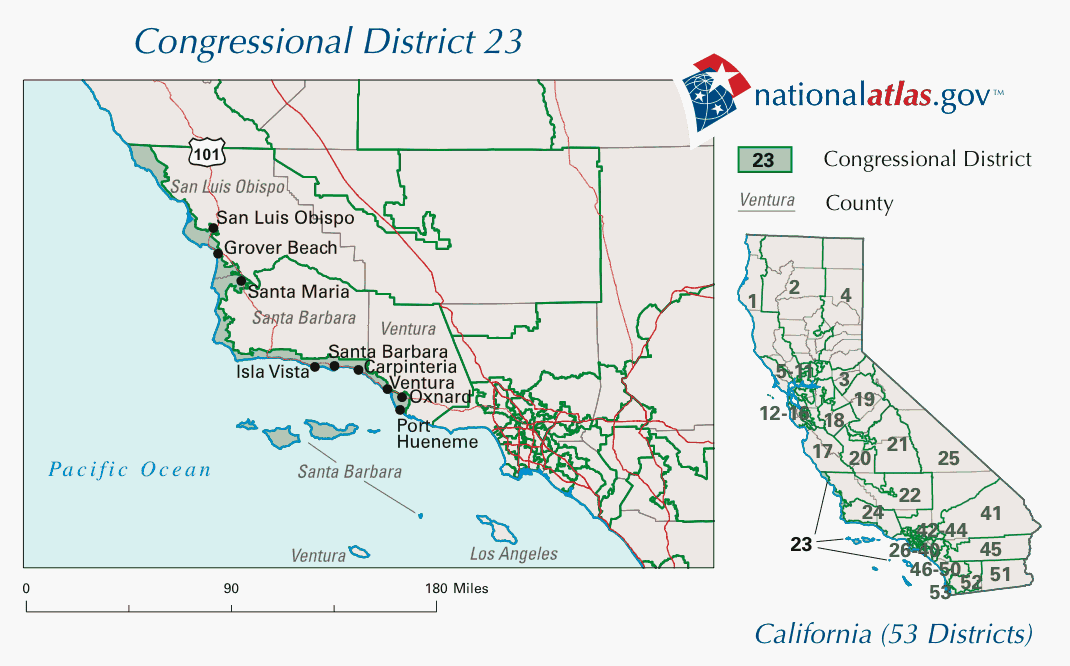

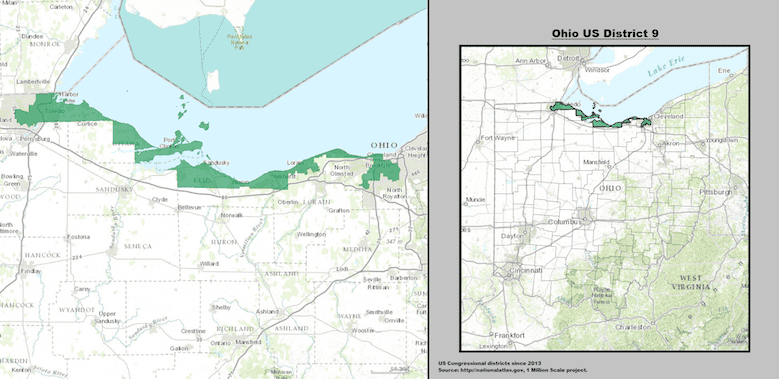

Let's look at another example. Historically, there have been a few long and skinny districts that would fail most tests for compactness. From 2003 to 2013, for instance, California's 23rd district covered hundreds of miles of Pacific coastline, but barely any land farther inland:

Ohio's 9th district currently has a similar shape; it hugs the southern edge of Lake Erie.

Are these districts further examples of partisan gerrymandering? Or were they created because coastal residents in these states are likely to have similar needs from their representatives? Looking just at the shapes of these districts, either possibility seems plausible.

For these reasons, compactness arguments haven't really held up in court battles fighting gerrymandering. It's simply too difficult to look at one district in isolation and prove that it was intentionally gerrymandered to favor one party over another.

Therefore, recent advances in gerrymandering detection have focused not on single districts, but on states as a whole. Forget about compactness; in fact, forget about the shape of the district entirely. If you can prove that there's a pattern of bias across many districts in favor of one party over another, there's your smoking gun.

Plenty of people have worked on developing objective mathematical measures that can assess whether or not a state has been excessively gerrymandered. A few different ideas have been explored, but one of the most popular new techniques is also relatively simple, and requires little more than basic arithmetic.

Quantifying Gerrymandering: The Efficiency Gap

Voting is inherently an inefficient mechanism for electing officials who represent the interests of a large group of people. This is because in most cases, the winner is determined by winner take all. In other words, a representative can win with 50.1% of the vote, even though that person is unlikely to represent the interests of 49.9% of the people in his or her district.

In this system, if your candidate loses, it's easy to think of your vote as being wasted, since the official who won and now represents you likely doesn't actually represent you. But people who vote for losing candidates aren't the only ones whose votes are wasted. Even votes for winners can be considered wasted, if they're in excess of the simple majority needed to squeeze out a win. In other words, if your candidate won by 10,000 votes, one could consider 9,999 of those votes "wasted," since the candidate still would've won even if the margin had been much smaller.

The efficiency gap is a gerrymandering metric that takes these observations into account. Essentially it calculates the number of wasted votes for each party, and determines whether there's a systemic bias towards wasted votes in one party compared to another.

This gap is calculated by counting the number of votes each party has wasted in each district. Once the total number of wasted votes has been found, we take the difference, and divide it by the total number of votes cast.

To see a sample calculation of the efficiency gap, please finish drawing your districts above.

This calculation has nothing to do with the shape of the districts, and everything to do with the resulting election outcome. When a collection of districts yield a high efficiency gap, does this mean that something sinister is going on with redistricting? In order to answer this question more fully, we need to take a look at how this metric fares against actual election data.

The Efficiency Gap in the Wild

Let's take a look at historical data on congressional elections in the United States.

In the map below, states are colored according to the size of the efficiency gap. Darker red indicates a larger efficiency gap favoring Republicans; darker blue indicates a larger efficiency gap favoring Democrats. You can examine results from every congressional election between 1996 and 2016. (If you're curious, you can see the raw data here.)

Note that it's impossible to gerrymander a state with only one representative, so those states are greyed out. For similar reasons, it's difficult to make compelling gerrymandering arguments for states with only a small handful of districts, and the efficiency gap is less powerful as a metric in such cases. For that reason, you can also choose to ignore states with a small number of districts (up to 10).

To the right of the map, there is bar chart of how the efficiency gap for each state translates into an expected advantage in terms of the number of congressional seats. The calculation here is straightforward: you just take the efficiency gap for a state and multiply by the number of districts in that state. I'm including this chart because authors Nicholas Stephanopoulos and Eric McGhee, who first introduced the efficiency gap, proposed the two-seat benchmark as a standard for throwing out a district map as being a partisan gerrymander. Lightly-colored bars correspond to states with a seat gap smaller than two; the fully-colored bars at the right are ones that exceed this two-seat threshold.

Take your time exploring the electoral landscape over time. What do you notice, and what questions come to mind?

Year: 2016

Minimum Number of Electors: 2

As you can see, states that have surpassed the two-seat threshold have almost exclusively benefitted Republican representation in congress. Moreover, since the last round of redistricting after the 2010 census, three states have have at least a two-seat Republican edge in the 2012, 2014, and 2016 elections: Pennsylvania, North Carolina, and Michigan. From this perspective, it's less surprising that the Pennsylvania state supreme court tossed out the congressional map earlier this year.

Caveats and Limitations

While the efficiency gap can help identify potentially problematic states, it's worth pointing out that the calculation itself has some limitations, both theoretical and practical. In no particular order, here are a few:

The focus of the efficiency gap is on the two-party system. When calculating the efficiency gap, then, third party votes are always discarded. In many races these votes are negligible, but not always. This becomes particularly problematic in races where neither the Democrat nor the Republican wins, in which case the votes for the winning candidate are ignored.

On the flip side, it's not true that every congressional race has a Democrat and a Republican on the ballot. In fact, in nearly 14% of the districts considered here (656 out of 4,708), either a Democrat or a Republican (or both) did not run. In such cases, I estimated the vote tallies based on vote tallies in surrounding years, as well as vote shares in nearby Presidential elections. But the efficiency gap relies on good historical data for its results, which can make its calculation more challenging than it might initially seem.

In our toy example at the start of this story we didn't have to deal with the issue of voter turnout. But in reality, district vote tallies won't always be the same, because turnout will vary. In order to ensure that higher-turnout districts don't skew the results, I first calculated the number of wasted votes per district as a percentage of wasted votes. I then calculated the efficiency gap based on these percentages. This is the same methodology used in Extreme Maps, a paper on gerrymandering by Laura Royden and Michael Li.

Speaking of Royden and Li, they also point out a couple of limitations with the efficiency gap. Here's one: "The efficiency gap rests on the assumption that for every 1 percent increase in vote share, a party should increase its seat share by 2 percent. For close states (where the winning party receives around 50 percent - 60 percent of the vote) this 1:2 ratio has historically been close to actual results for most maps but much less accurate when the winning party receives more than 60 percent of the vote. This makes the efficiency gap a fairly accurate measure for closely contested states but often much less of one for states dominated by one political party." Massachusetts is a good example here. The state as a whole leans heavily Democratic, so when the efficiency gap suggests partisan gerrymandering in the state, this may not be quite right.

Here's another, again from Royden and Li: "The efficiency gap can also be quite sensitive over time, fluctuating wildly between elections under the same map. States with even a few close districts can see significant swings — sometimes up to multiple seats in the seat gap results — in subsequent elections whose raw vote totals are only slightly different if even one district flips parties, and this volatility can make the efficiency gap problematic to use long-term over a series of years or decades."

Here's a fun math fact: a paper posted in October 2017 proved that the desired goals of creating districts that are (a) roughly the same size, (b) relatively compact, and (c) have a tolerable efficiency gap are mutually incompatible. See An impossibility theorem for gerrymandering for more details.

Conclusion

Gerrymandering is a thorny problem, and I've only outlined a couple of proposals for detecting it. There are certainly more if you'd like to dig deeper. Some other interesting proposals for addressing gerrymandering include use of the shortest splitline algorithm, as well as recent advances involving geometry and differential equations.

Others have argued that gerrymandering is but a symptom of a different problem: our gradual self-selection into liberal groups concentrated in cities, and conservative groups concentrated in more rural areas. The thinking here is that it's easier to gerrymander a population that's already divided itself, and according to some analyses, like this one from FiveThirtyEight, gerrymandering is taking too much of the blame for our current political polarization:

Regardless of how pervasive a problem it is, reduction in gerrymandering is one of the few issues that enjoys broad bipartisan support. Here's hoping that the next few years will see mathematics used on the right side of this fight, rather than being used to draw even more extreme gerrymanders in the future.

Finally, it's important to note that even if citizens are able to combat gerrymandering through their legislatures, or even overcome the inherent bias in gerrymandered districts through increased voter turnout, gerrymandering is but one of many strategies those in power use to try to maintain their power. Equally as important, if not more so, are continued and systematic efforts at voter suppression. We also need to be vigilant in defending against more fundamental attempts to bias our representation at the census level itself.

But these are topics for another day. If you'd like to learn more about gerrymandering, please check out some of the sources below. And if you can, don't forget to vote!

Sources:

- Efforts to limit partisan gerrymandering falter at Supreme Court, by Robert Barnes.

- Pennsylvania Supreme Court draws 'much more competitive' district map to overturn Republican gerrymander, by Christopher Ingraham.

- Drive Against Gerrymandering Finds New Life in Ballot Initiatives, by Michael Wines.

- Congressional Redistricting and Gerrymandering, by David Austin.

- Extreme Maps, by Laura Royden and Michael Li.

- What Does Compactness Really Mean?, by Evelyn Lamb.

- America's Most Gerrymandered Congressional Districts, by Christopher Ingraham.

- Partisan Gerrymandering and the Efficiency Gap, by Nicholas Stephanopoulos and Eric McGhee.

- An impossibility theorem for gerrymandering, by Boris Alexeev and Dustin G. Mixon.

- Gerrymandering and a cure for it – the shortest splitline algorithm (executive summary), by Warren D. Smith.

- Mathematicians invent tool to judge when voting maps have been unfairly drawn, by the University of Vermont.

- A partial differential equations approach to defeating partisan gerrymandering, by Matt Jacobs and Olivia Walch.

Here are some other stories you may like:

Strength in Numbers

April 2019 - 9 minute read

Exploring American voting trends in the 21st century.

Dishing on Petrie

April 2018 - 9 minute read

Mathematical models of toxic tech culture.

Laws of Inequality

January 2018 - 10 minute read

Exploring income and wealth inequality through physics.