Laws of Inequality

January 2018

It's a well-established fact that in the United States, income inequality is increasing. According to a 2011 report from the Congressional Budget Office, between 1979 and 2011 income for the top 1% of households grew by 275%. Meanwhile, for the bottom 20%, income grew by only 18%.

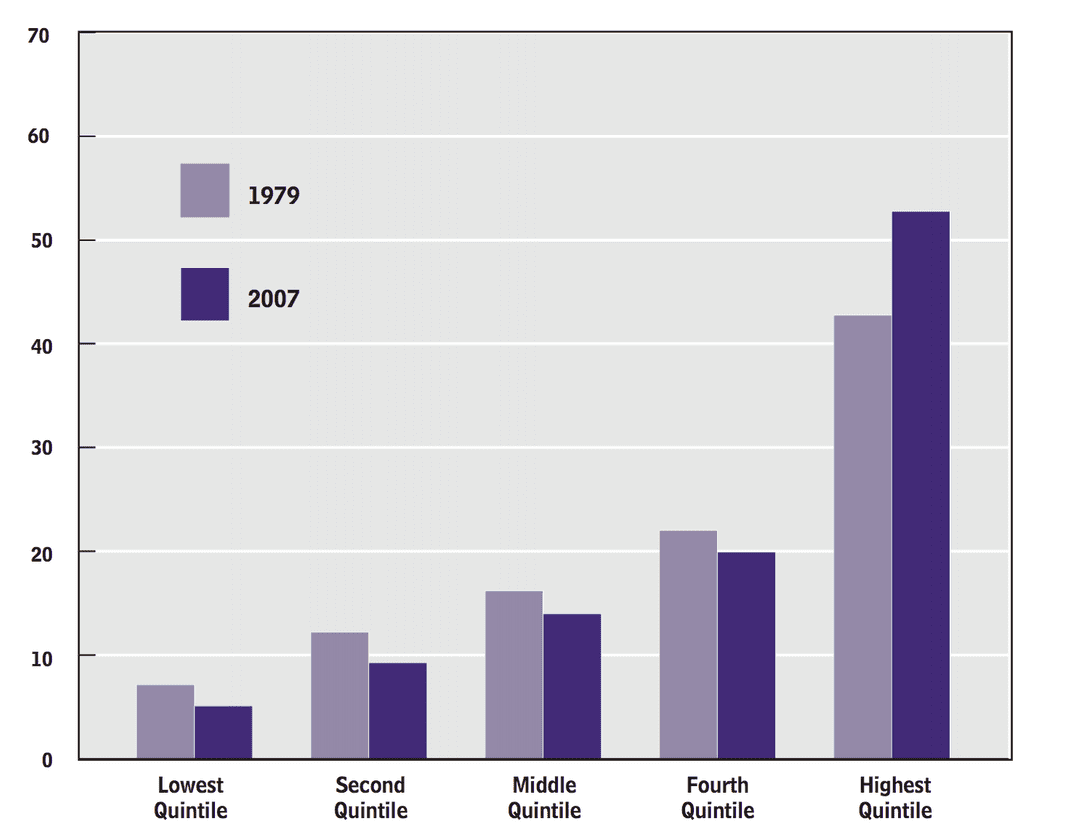

Looking at different income groups' share of total income tells a similar story. In 1979, the top 1% of earners accounted for 9.6% of total household income in the United States. The top 20% of earners accounted for just under 45.7% of total household income, while the bottom 20% accounted for around 7.7%.

By 2007, this gap had significantly widened. The top 20% of earners increased their share of the pie by almost ten points, to 55%. This increase is almost entirely explained by huge gains by the top 1%, who saw their income share nearly double to 18.6%. Meanwhile, the bottom 20% of earners saw their share decrease two points, to 5.7%. And given current trends over the past decade, it's hard to imagine the picture has gotten much rosier for most Americans.

As the income gap grows, so too does the wealth gap, which measures a family's total assets. According to a 2016 CBO report, the top 10% of families held 76% of the overall wealth in the United States in 2013, up from 67% in 1989. In contrast, the bottom 50% of families held only 1% of the total wealth in 2013, down from 3% in 1989.

When it comes to income and wealth inequality in America, we're moving in the wrong direction. Worldwide, the picture isn't much better: according to a recent Oxfam report, 82% of the wealth created in 2017 went to wealthiest 1%.

I'm not an economist or a policy maker; I have no idea what steps we could take to begin reversing the trend that has emerged over the past 40 years. I am a mathematician, though, so instead I'd like you to consider a thought experiment.

Starting from Scratch

Let's imagine that we could blow away all of the complexities in our economy, and create a society where everyone starts out with an equal amount of wealth. The economy is strictly based on bartering: whenever two people meet, they can decide to trade goods between them. This exchange will, of course, have an affect on each individual's wealth.

When two people successfully barter, presumably they both feel good about the exchange, otherwise they wouldn't go through with it. But it's unlikely that the trade is entirely equal. It's much more likely that after the exchange, one person will have gained some wealth, while the other person will have lost some.

However, to keep things from getting out of hand, there's no concept of debt in our society. When two people meet to barter, the value that they're bartering can never exceed the poorer individual's wealth.

We can summarize the rules of this society as follows:

- Everyone starts out with the same amount of wealth.

- The distribution of wealth evolves through a sequence of trades between randomly selected pairs of citizens.

- The amount of the trade is also random, but can never exceed the wealth of the person who has less.

I was first introduced to this idea by mathematician Brian Hayes in his book, Group Theory in the Bedroom, and Other Mathematical Diversions. What first interested me in this hypothetical society is how fair it sounds. Everyone starts out on exactly the same footing, and the rules of the game seem about as fair as can be. Everyone trades in good faith, and nobody can run up a debt by doing so.

If you take a moment to think about how this society is likely to evolve, you might convince yourself that people in the society should behave like gas particles, randomly colliding with one another and exchanging energy. Except instead of energy, these people are exchanging their wealth. Here's what such a simulation might look like:

Population Size

Figure 1: Here's how you might expect our model society to evolve.

In the above simulation, each person's wealth is visualized both by his or her speed and by his or her color. Faster circles correspond to wealthier individuals and have a red color, while slower circles correspond to less wealthy individuals and take on more of a blue hue.

If you take a look at the bar graph while time passes, you should see a relatively smooth distribution of wealth, from the poorest on the left to the wealthiest on the right. The distribution certainly highlights inequality, but not necessarily an unfair degree of it. After all, we probably want a certain degree of inequality, as long as upwards mobility is still within our citizens' grasp. And indeed, this society is highly mobile: with enough people, the poorest person is rarely the poorest for very long, and similarly for the richest person.

Unfortunately, this isn't how our model society actually evolves.

Trickle-Up Economics

Here's what actually happens to society based on our simple bartering rules:

Population Size

Figure 2: Here's how our model society actually evolves.

Unlike gas particles bumbling around together, this time one citizen gradually leeches the wealth away from everyone else. Eventually, almost everyone lives in extreme poverty, with one lucky individually accumulating all of the wealth in the society.

This result is initially surprising for many people (myself included), in large part because the rules seem entirely reasonable and fair. But even for relatively simple systems like this hypothetical society, fair rules do not necessarily yield desirable outcomes. Even if we all agree that the rules of this society seem fair, I don't think any of us would want to live in a society governed by these rules.

How is it that a system with such a fair set of rules can lead to such extreme inequality? One simple way to understand it is with a small society of only two people. In this scenario, there's no randomness in who will be doing the trading.

Consider what happens when these people meet for the first time to trade. In this case, they begin with an equal amount of wealth. And it's possible that the value of the trade will be small, but it's also quite likely that the value will be relatively large. More precisely, since both parties have the same amount of wealth, there's a 50% chance that someone will walk away from the trade with at least half of their wealth depleted.

To keep things simple, let's say each person has 100 units of wealth, and the value of the trade winds up being 50. After the trade, one person will walk away with 150 units of wealth, and the other will wind up with 50.

But the next time the two meet to trade, there's a problem. The maximum value of the trade is now much lower: 50 units of wealth instead of 100. Our rule about capping the value of the trade, which seems entirely reasonable at the outset, winds up restricting everyone's ability to regain wealth they've lost. For this second trade, one person could potentially lose almost everything, while the other person will lose at most one third of their wealth.

Taken to the extreme, you can see how it's almost impossible to regain a significant amount of wealth after it's been depleted. If one party has 199 units of wealth and the other party has only 1, it's practically impossible for the second person to climb out of poverty.

Maybe Robin Hood was Right

It's worth pointing out that the first simulation, the one that yields a fairer distribution of wealth, stems from rules that at the outset seem less fair. The rules are quite similar to the ones mentioned above, but with an important change to the last rule:

- Everyone starts out with the same amount of wealth.

- The distribution of wealth evolves through a sequence of trades between randomly selected pairs of citizens.

- The amount of the trade is also random, but can never exceed the wealth of the person who

has lessloses wealth in the trade.

Let's see how this plays out in our previous example, with a two-person society. If the first trade has a value of 50, then one person will walk away with 150 units of wealth, and the second will have only 50 remaining. However, unlike before, now when the second trade happens, the poorer person has a much better chance of recouping some real wealth. Of course, if the poorer person loses the trade, they will continue to decrease their wealth. But if they win, they can now win as many as 150 units of wealth, rather than just the 50 they could have won before.

Even in an extreme case, the poorest person still has reason to hope. In the case where one person has 199 units of wealth to the other person's 1, the poor person is still quite likely to recoup a significant amount of wealth as soon as they win a trade. Making the value of the trade based on how much the loser has, rather than based on how much the poorest person has, means that wealth flows much more freely between people.

Conceptually, though, this is perhaps a little troubling. While it's nice to imagine a society altruistic enough that the wealthy would so willingly give to the poor, a more sensible interpretation is also much more sinister. In his book, Hayes offers the following take:

A distinctive characteristic of the trading scheme is that the richer party always has more to lose and the poorer has more to gain. Under these terms, any sensible person would try to do business only with the wealthier partners, and no one would ever willingly choose to trade with a less-affluent person (assuming traders can gauge the wealth of their partners). Thus if trading between non-equals takes place at all, it must be by coercion or deception. In other words, what is being modeled here is theft and fraud.

Can less fair behavior locally (i.e. stealing from individuals) lead to fairer societies globally? If so, maybe Robin Hood was onto something.

Fitness Test

But before you rush into the streets and start smashing windows to take whatever you like, it's worth pausing and thinking about how much this model has to say about our actual reality. It's quite possible that this model doesn't fit reality very well at all.

The biggest reason to be skeptical of these models is that they're much simpler than our actual society. The model eliminates all goods, so that these trades are based on wealth alone. The model is also a closed system; consequently, new wealth is never created, nor is it ever taken by some larger structure (e.g. a government imposing taxes). The population is also unchanging, and so questions of how wealth should be transferred from one generation to the next have no bearing on the model.

On the other hand, all models are simplifications, so throwing out the model because it isn't a perfect reflection of society seems a bit extreme. Instead, maybe we can meet somewhere in the middle: by taking a look at the data on income and wealth in America, maybe we can tease out some features of the model that may provide real insight, in spite of the simplifications.

And indeed, studies based on tax return data suggest that these models may have kernels of truth in them. In Evidence for the exponential distribution of income in the USA, for instance, the authors analyze IRS data from 1979-1997, and conclude that the distribution of income over time seems to closely resemble the distribution of energy in gas particles, not unlike our first demonstration above.

While these models certainly leave much to be desired in terms of their realism, I don't think it's fair to conclude that nothing can be gained from them.

Saving the Models

If you'd like to sprinkle just a little bit more realism into the model, there are many directions you can go. For instance, there are models in which the probability of winning a trade isn't 50/50. Instead, people with more wealth are more likely to win the trade, the reasoning being that they're more powerful or influential than the other party.

You can also try to incorporate savings into the model, whereby people set aside a certain fraction of their wealth before each time they trade. Here's a demonstration of how that model evolves. The trading value is based on the losing party's wealth, not on the poorer person's wealth, and before the simulation starts, you can adjust what fraction of their wealth people will save:

Population Size

Savings Rate

Figure 3: Here's a model based on theft and savings.

The outcome here isn't drastically different than before, but by increasing the savings rate, we can reduce inequality. In fact, if everyone saves 100% of their wealth, no wealth is ever transferred! While this isn't super realistic, it is interesting to note that encouraging savings helps decrease the spread between the haves and the have-nots.

It's also worth pointing out that models involving savings also appear to have a basis in reality. This may seem somewhat surprising, since the model sets one savings rate for the entire population. But for groups of people who work similar jobs, this assumption yields a model that may have some truth in it. More specifically, in Kinetic Exchange Models for Income and Wealth Distributions, the authors write that for waged income of factory workers in the UK and the USA, and among college students in the USA, the distributions are similar, and can be modeled with some accuracy using the idea of a single savings rate parameter for the entire population.

Conclusion

Income and wealth inequality are just a couple of the crises we're facing, and thus far we're doing a pretty terrible job making things better. It's easy to throw up our hands when faced with issues that are so complex and seemingly intractable. But in these cases, simple models can help. They may not tell us the whole story, but they can tell us a part. And once we understand that part, it's often easier to grapple with enhancements that make the model more realistic, but also more complex.

If you're looking to take these ideas even further, check out some of the links below. Otherwise, feel free to stick around here and watch circles bounce around in an enclosed space. I can't be the only one who finds it mesmerizing.

Sources

- Trends in the Distribution of Household Income Between 1979 and 2007

- Trends in Family Wealth, 1989 to 2013

- Statistical mechanics of money

- Evidence for the exponential distribution of income in the USA

- Emergent Statistical Wealth Distributions in Simple Monetary Exchange Models: A Critical Review

- Kinetic Exchange Models for Income and Wealth Distributions

For those curious about the visualizations:

Here are some other stories you may like:

Dishing on Petrie

April 2018 - 9 minute read

Mathematical models of toxic tech culture.

Mind the Gerrymandered Gap

October 2018 - 13 minute read

An interactive introduction to gerrymandering.

The Fairest of Them All

January 2019 - 15 minute read

A mathematical exploration of fairness.